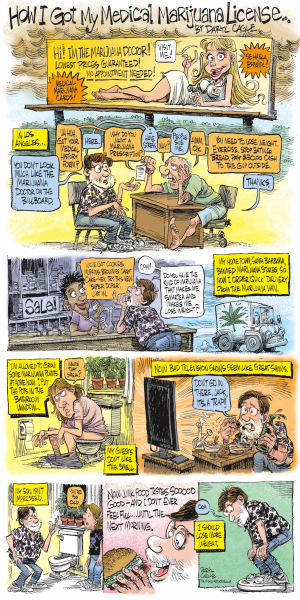

Read This Column About Political Cartoons – Then Write About Something Else

As a political cartoonist, I’d like to think my cartoons influence public opinion, but that rarely happens. People love a cartoon that they already agree with, and hate cartoons that they already disagree with. Editors like to choose editorial cartoons that they know their readers will like, so cartoons end up being a reflection of public opinion. In fact, political cartoons offer a great historical tool, giving a true picture of the opinions and emotions of a society at any given time.

Historians seem to have discovered political cartoons only recently, and I’ve started seeing a steady stream of scholarly papers about my profession as college professors and students suddenly look to my work and the work of my colleagues to support their political positions. One widely held canard seems to be popular among the academics: that the world supported the USA after 9/11 and this support was then squandered by the Bush administration’s adventures in the Middle East.

Academics like to look at the cartoons drawn immediately after the 9/11 attack where, around the world, almost every editorial cartoonist drew the same image of a weeping Statue of Liberty. I drew one too. In fact, most cartoonists are ashamed of their weeping statues; we wish we could have a “do-over” where we wouldn’t draw the first image to come to mind. Newspaper columnists all wrote much the same column right after 9/11, but it is easier to notice matching cartoons than matching columns, so cartoonists get the bad rap for “group-think.” Even so, our matching cartoons were what the public wanted to see at that time and I probably received more mail from readers who loved my weeping Liberty than any other cartoon I’ve drawn.

International political cartoonists revile the USA in a uniform drumbeat of daily digs at America. The academics don’t notice that international political cartoons before 9/11 were almost as negative about America as the cartoons now. After our matching, weeping statues, the American and international cartoonists diverged. On 9/12, American cartoonists started drawing patriotic cartoons portraying resolve, strength, and the virtues of the New York Fire and Police Departments, standing tall as twin towers. American cartoonists drew scores of images of a strong Uncle Sam, threatening eagles and a newly militant Statue of Liberty, demanding revenge.

Just after 9/11 the international cartoonists depicted the irony of mighty America put in its place. A favorite, foreign symbol for America is Superman, and we saw scores of images showing both Superman and Uncle Sam defeated, injured, bleeding and grieving. The worldwide cartoonists treated 9/11 in the way that tabloids treat fallen celebrities: with delight in the spectacle of a beautiful actress who is overweight, or getting a messy divorce — or better yet, caught in a drunken scene, screaming racial epithets so that we can see that the rich, powerful, famous, conceited, fallen star was a hypocrite all along.

Some international cartoonists wrote to me about the patriotic cartoons; they couldn’t believe American cartoonists would choose to draw such cartoons by their own free will; we must have been directed to draw that nonsense by the Bush Administration. Academics have picked up on the idea of “self-censorship;” that cartoonists somehow didn’t draw what they wanted to draw because the country wasn’t ready for jokes, or editors didn’t want to see criticism of the Bush administration at a time when we all had to pull together.

In fact, the system worked as it always had: some cartoonists criticized the government right away, some cartoonists were joking immediately, most cartoonists held the same opinions as their readers, editors selected cartoons they agreed with and thought their readers would agree with. Newspapers ended up printing cartoons that accurately reflected public opinion, both here and abroad.

I have a few words for the professors and college students:

1.) Editorial cartoons show that the rest of the world didn’t like America before 9/11; they didn’t like us just after 9/11; and they still don’t like us.

2.) The government doesn’t control or intimidate American cartoonists or editors, now or then. Yes, we really believe what we say in our cartoons. No, cartoonists are not hampered by self-censorship.

3.) Please don’t ask me to comment on your paper, thesis or dissertation about editorial cartoons. Just read this column, then write about something else.

Daryl Cagle is a political cartoonist and blogger for MSNBC.com. He is a past president of the National Cartoonists Society and his cartoons are syndicated to more than 800 newspapers, including the paper you are reading. His books “The BIG Book of Bush Cartoons” and “The Best Political Cartoons of the Year, 2005, 2006 and 2007 Editions,” are available in bookstores now. Copyright 2007 Cagle Cartoons Inc. Please contact Sales at [email protected] for reproduction rights.